Summary

Cricket is a bat and ball game, played between two teams of eleven players each.[19][20] One team bats, attempting to score runs, while the other bowls and fields the ball, attempting to restrict the scoring and dismiss the batsmen. The objective of the game is for a team to score more runs than its opponent. In some forms of cricket, it may also be necessary to dismiss the opposition in order to win the match, which would otherwise be drawn.

There are separate leagues for Women's cricket, though informal matches may have mixed teams.

Format of the game

A cricket match is divided into periods called innings (which ends with "s" in both singular and plural form). It is decided before the match whether the teams will have one innings or two innings each. During an innings one team fields and the other bats. The two teams switch between fielding and batting after each innings. All eleven members of the fielding team take the field, but only two members of the batting team (two batsmen) are on the field at any given time. The order of batsmen is usually announced just before the match, but it can be varied.

A coin toss is held by the team captains (who are also players) just before the match starts: the winner decides whether to bat or field first.

The cricket field is usually oval in shape, with a rectangular pitch at the center. The edge of the playing field is marked with a boundary, which could be a fence, part of the stands, a rope or a painted line.

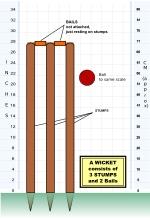

At each end of the pitch is a wooden target called a wicket, placed 22 yards apart. The pitch is marked with painted lines: a bowling crease in line with the wicket, and a batting or popping crease four feet in front of it. The wicket is made of three vertical stumps supporting two small horizontalbails. A wicket is put down if at least one bail is dislodged, or one stump is knocked down (usually by the ball, but also if the batsman does it with his body, clothing or equipment). This is also described as breaking, knocking down, or hitting the wicket -- though if the ball hits the wicket but does not dislodge a bail or stump then it is not down.

At any instant each batsman owns a particular wicket (usually the one closest to him) and, except when actually batting, is safe when he is in his ground. This means that at least one part of his body or bat is touching the ground behind the popping crease. If his wicket is put down while the ball is live and he is out of his ground then he is dismissed, but the other batsman is safe.[21]

The two batsmen take positions at opposite ends of the pitch. One designated member of the fielding team, called the bowler, bowls the ball from one end of the pitch to the striking batsman at the other end. (The batsman at the bowling end is called the non-striker, and stands to the side of his wicket, behind his crease. The batsman are allowed to step forward of their creases, though at some risk. Another member of the fielding team, the wicket keeper, is positioned behind the striker's wicket.

The fielding team's other nine members stand outside the pitch, spread out across the field. The fielding captain often strategically changes their position between balls.

There is always an umpire at each end of the pitch.

The bowler usually retreats a few yards (meters) behind the wicket, runs towards it (his run-up), and then releases the ball over-hand as he reaches the bowling crease. (If he crosses the crease before he releases the ball, or if he flexes his elbow too much in a throw, then it is a no ball, and the batting team gets a penalty or extra run. If the ball passes the far wicket out of reach of the batsman then it is called a wide, also with an extra run.) The ball can be bowled so that it bounces on the pitch, lands exactly on the crease (a yorker), or crosses the crease without bouncing (afull toss).

The batsman tries to prevent the ball from hitting the wicket by striking the ball with his bat. (This includes the handle of the bat, and his gloves.) If the bowler succeeds in putting down the wicket the batsman is dismissed and is said to be bowled out. If the batsman misses the ball, but any part of his body prevents it from reaching the wicket, then he is out leg before wicket, or "LBW".

If the batsman hits the ball but it is caught by a fielder without bouncing then he caught out. If it is caught by the bowler then he is caught and bowled; by the wicket keeper, caught behind.

If the batsman is successful in striking the ball and it is not caught without bouncing, then the two batsmen may try to score points (runs) for their team. Both batsmen run the length of the pitch, exchanging positions, and grounding their bats behind the opposite crease. Each crossing and grounding by both batsmen is worth one run. The batsmen may attempt one run, multiple runs, or elect not to run at all. By attempting runs, the batsmen risk dismissal. This happens if the fielding team retrieves the ball and hits either wicket with the ball (either by throwing it, or while holding it) before the batsman who owns that wicket reaches his ground behind the crease. The dismissed batsman is run out. Batsmen will sometimes start to run, change their mind, and return to their original positions.

If the batsman hits the ball over the field boundary without the ball touching the field, the batting team scores six runs. If the ball touches the ground and then reaches the boundary, the batting team scores four runs. The batsmen might start running before the ball reaches the boundary, but those runs don't count.

If the batsman misses the ball they can still attempt extra runs : these are called byes. If the ball bounces off his body then it is called a leg bye.

If the striking batsman leaves his ground and misses the ball, then the wicket keeper can catch it and put down the wicket -- stumped.

In case of a no ball or a wide the batsman can choose to strike the ball, earning runs in addition to the fixed penalty. If he does so he can only be dismissed by being run out.

When the batsmen have finished attempting their runs the ball is dead, and is returned to the bowler to be bowled again. The ball becomes live when he starts his run up. The bowler continues to bowl toward the same wicket, regardless of any switch of the batsmen's positions.[22]

A batsman may retire from an innings without being dismissed, usually after reaching a milestone like a hundred runs (a century).

A dismissed batsman leaves the field, to be replaced by another batsman from the batting team. However, even though the wicket may have been put down, or the ball caught, the batsman is not actually dismissed until the fielding team appeal to the umpires for a decision, traditionally using the expression "How's that" (or "Howzat"). In some matches, particularly test matches, either team may request a review by a third umpire who can use a Decision Review System (DRS), which includes TV replays and other electronic equipment such as hawk eye, hotspot and thesnickometer.

After a bowler has bowled six times (an over), another member of the fielding team is designated as the new bowler, the old bowler taking up a fielding position. The batsmen stay in place, and the new bowler bowls to the opposite wicket, so the role of striker and non-striker reverse. The wicket keeper and the two umpires always change positions, as do many of the fielders, and play continues. Fielding team members may bowl multiple times during an innings, but may not bowl two overs in succession.

The innings is complete when 10 of the 11 members of the batting team have been dismissed (all out -- although one always remaining "not out"), when a set number of overs has been played, or when the batting team declares that they have enough runs.

The number of innings and the number of overs per innings vary depending on the format of the match. In a match which is not a limited overs format the umpires will usually specify that the last session of the last innings will have a specified number of overs.

The match always ends when all innings have been completed. The umpires can also call an end to the match in case of bad light or weather. But in many cases the match ends immediately when the first team to bat has played all of its innings, and the last team to bat has more runs. In four-innings games the last team may not even need to play its second innings: this team is said to win by an innings. If this winning team has not completed its last innings, and still has, for example, five batsmen who are not out or have not even batted, then they are said to "win by five wickets". If the last team to bat is losing, is all out, and has 10 fewer runs than the other team, then the winning team "wins by 10 runs". If the two teams both play all their innings and they have the same number of runs, then it is a tie.

In four-innings matches there is also the possibility of a draw: the team with fewer runs still has batsmen on the field when the game ends. This has a major effect on strategy: a team will often declare an innings when they have accumulated enough runs, in the hope that they will have enough time left to dismiss the other team and thus avoid a draw, but risking a loss if the other team scores enough runs.

Pitch, wickets and creases

See also: Stump (cricket) and Bail (cricket)

Playing surface

Cricket is played on a grassy field.[23] The Laws of Cricket do not specify the size or shape of the field,[24] but it is often oval. In the centre of the field is a rectangular strip, known as the pitch.[23]

The pitch is a flat surface 10 feet (3.0 m) wide, with very short grass that tends to be worn away as the game progresses.[25] At either end of the pitch, 22 yards (20 m) apart, are placed wooden targets, known as the wickets. These serve as a target for the bowling (also known as the fielding) side and are defended by the batting side, which seeks to accumulate runs.

Stumps, bails and creases

Each wicket on the pitch consists of three wooden stumps placed vertically, in line with one another. They are surmounted by two wooden crosspieces called bails; the total height of the wicket including bails is 28.5 inches (720 mm) and the combined width of the three stumps, including small gaps between them is 9 inches (230 mm).

Four lines, known as creases, are painted onto the pitch around the wicket areas to define the batsman's "safe territory" and to determine the limit of the bowler's approach. These are called the "popping" (or batting) crease, the bowling crease and two "return" creases.

The stumps are placed in line on the bowling creases and so these creases must be 22 yards (20 m) apart. A bowling crease is 8 feet 8 inches (2.64 m) long, with the middle stump placed dead centre. The popping crease has the same length, is parallel to the bowling crease and is 4 feet (1.2 m) in front of the wicket. The return creases are perpendicular to the other two; they are adjoined to the ends of the popping crease and are drawn through the ends of the bowling crease to a length of at least 8 feet (2.4 m).

When bowling the ball, the bowler's back foot in his "delivery stride" must land within the two return creases while at least some part of his front foot must land on or behind the popping crease. If the bowler breaks this rule, the umpire calls "No ball".

The importance of the popping crease to the batsman is that it marks the limit of his safe territory. He can be dismissed stumped or run out (see Dismissals below) if the wicket is broken while he is "out of his ground".

Bat and ball

Main articles: Cricket bat and Cricket ball

The essence of the sport is that a bowler delivers the ball from his end of the pitch towards the batsman who, armed with a bat is "on strike" at the other end.

The bat is made of wood (usually White Willow) and has the shape of a blade topped by a cylindrical handle. The blade must not be more than 4.25 inches (108 mm) wide and the total length of the bat not more than 38 inches (970 mm).

The ball is a hard leather-seamed spheroid, with a circumference of 9 inches (230 mm). The hardness of the ball, which can be delivered at speeds of more than 90 miles per hour (140 km/h), is a matter for concern and batsmen wear protective clothing including pads (designed to protect the knees and shins), batting gloves for the hands, a helmet for the head and a box inside the trousers (to protect the crotch area). Some batsmen wear additional padding inside their shirts and trousers such as thigh pads, arm pads, rib protectors and shoulder pads. The ball has a "seam": six rows of stitches attaching the leather shell of the ball to the string and cork interior. The seam on a new ball is prominent, and helps the bowler propel it in a less predictable manner. During cricket matches, the quality of the ball changes to a point where it is no longer usable, and during this decline its properties alter and thus influence the match.

Umpires and scorers

Main articles: Umpire (cricket) and Scorer

The game on the field is regulated by two umpires, one of whom stands behind the wicket at the bowler's end, the other in a position called "square leg", a position 15–20 metres to the side of the "on strike" batsman. The main role of the umpires is to adjudicate on whether a ball is correctly bowled (not a no ball or a wide), when a run is scored, and whether a batsman is out (the fielding side must appeal to the umpire, usually with the phrase How's That?). Umpires also determine when intervals start and end, decide on the suitability of the playing conditions and can interrupt or even abandon the match due to circumstances likely to endanger the players, such as a damp pitch or deterioration of the light.

Off the field and in televised matches, there is often a third umpire who can make decisions on certain incidents with the aid of video evidence. The third umpire is mandatory under the playing conditions for Test matches and limited overs internationals played between two ICC full members. These matches also have a match referee whose job is to ensure that play is within the Laws of cricket and the spirit of the game.

The match details, including runs and dismissals, are recorded by two official scorers, one representing each team. The scorers are directed by the hand signals of an umpire. For example, the umpire raises a forefinger to signal that the batsman is out (has been dismissed); he raises both arms above his head if the batsman has hit the ball for six runs. The scorers are required by the Laws of cricket to record all runs scored, wickets taken and overs bowled; in practice, they also note significant amounts of additional data relating to the game.

Innings

The innings (ending with 's' in both singular and plural form) is the term used for the collective performance of the batting side.[26] In theory, all eleven members of the batting side take a turn to bat but, for various reasons, an innings can end before they all do so. Depending on the type of match being played, each team has one or two innings apiece.

The main aim of the bowler, supported by his fielders, is to dismiss the batsman. A batsman when dismissed is said to be "out" and that means he must leave the field of play and be replaced by the next batsman on his team. When ten batsmen have been dismissed (i.e., are out), then the whole team is dismissed and the innings is over. The last batsman, the one who has not been dismissed, is not allowed to continue alone as there must always be two batsmen "in". This batsman is termed "not out".

An innings can end early for three reasons: because the batting side's captain has chosen to "declare" the innings closed (which is a tactical decision), or because the batting side has achieved its target and won the game, or because the game has ended prematurely due to bad weather or running out of time. In each of these cases the team's innings ends with two "not out" batsmen, unless the innings is declared closed at the fall of a wicket and the next batsman has not joined in the play.

In limited overs cricket, there might be two batsmen still "not out" when the last of the allotted overs has been bowled.

Overs

Main article: Over (cricket)

The bowler bowls the ball in sets of six deliveries (or "balls") and each set of six balls is called an over. This name came about because the umpire calls "Over!" when six balls have been bowled. At this point, another bowler is deployed at the other end, and the fielding side changes ends while the batsmen do not. A bowler cannot bowl two successive overs, although a bowler can bowl unchanged at the same end for several overs. The batsmen do not change ends and so the one who was non-striker is now the striker and vice-versa. The umpires also change positions so that the one who was at square leg now stands behind the wicket at the non-striker's end and vice-versa.

Team structure

A team consists of eleven players. Depending on his or her primary skills, a player may be classified as a specialist batsman or bowler. A well-balanced team usually has five or six specialist batsmen and four or five specialist bowlers. Teams nearly always include a specialist wicket-keeper because of the importance of this fielding position. Each team is headed by a captain who is responsible for making tactical decisions such as determining the batting order, the placement of fielders and the rotation of bowlers.

A player who excels in both batting and bowling is known as an all-rounder. One who excels as a batsman and wicket-keeper is known as a "wicket-keeper/batsman", sometimes regarded as a type of all-rounder. True all-rounders are rare as most players focus on either batting or bowling skills.

Bowling

The bowler reaches his delivery stride by means of a "run-up", although some bowlers with a very slow delivery take no more than a couple of steps before bowling. A fast bowler needs momentum and takes quite a long run-up, running very fast as he does so.

The fastest bowlers can deliver the ball at a speed of over 90 miles per hour (140 km/h) and they sometimes rely on sheer speed to try and defeat the batsman, who is forced to react very quickly. Other fast bowlers rely on a mixture of speed and guile. Some fast bowlers make use of the seam of the ball so that it "curves" or "swings" in flight. This type of delivery can deceive a batsman into mistiming his shot so that the ball touches the edge of the bat and can then be "caught behind" by the wicketkeeper or a slip fielder.

At the other end of the bowling scale is the "spinner" who bowls at a relatively slow pace and relies entirely on guile to deceive the batsman. A spinner will often "buy his wicket" by "tossing one up" (in a slower, higher parabolic path) to lure the batsman into making a poor shot. The batsman has to be very wary of such deliveries as they are often "flighted" or spun so that the ball will not behave quite as he expects and he could be "trapped" into getting himself out.

In between the pacemen and the spinners are the "medium pacers" who rely on persistent accuracy to try and contain the rate of scoring and wear down the batsman's concentration.

All bowlers are classified according to their looks or style. The classifications, as with much cricket terminology, can be very confusing. Hence, a bowler could be classified as LF, meaning he is a left arm fast bowler; or as LBG, meaning he is a right arm spin bowler who bowls deliveries that are called a "leg break" and a "Googly".

During the bowling action the elbow may be held at any angle and may bend further, but may not straighten out. If the elbow straightens illegally then the square-leg umpire may call no-ball: this is known as "throwing" or "chucking", and can be difficult to detect. The current laws allow a bowler to straighten his arm 15 degrees or less.

Fielding

Main articles: Fielding (cricket) and Fielding strategy (cricket)

All eleven players on the fielding side take the field together. One of them is the wicket-keeper aka "keeper" who operates behind the wicket being defended by the batsman on strike. Wicket-keeping is normally a specialist occupation and his primary job is to gather deliveries that the batsman does not hit, so that the batsmen cannot run byes. He wears special gloves (he is the only fielder allowed to do so), a box over the groin, and pads to cover his lower legs. Owing to his position directly behind the striker, the wicket-keeper has a good chance of getting a batsman out caught off a fine edge from the bat. He is the only player who can get a batsman out stumped.

Apart from the one currently bowling, the other nine fielders are tactically deployed by the team captain in chosen positions around the field. These positions are not fixed but they are known by specific and sometimes colourful names such as "slip", "third man", "silly mid on" and "long leg". There are always many unprotected areas.

The captain is the most important member of the fielding side as he determines all the tactics including who should bowl (and how); and he is responsible for "setting the field", though usually in consultation with the bowler.

In all forms of cricket, if a fielder gets injured or becomes ill during a match, a substitute is allowed to field instead of him. The substitute cannot bowl, act as a captain or keep wicket. The substitute leaves the field when the injured player is fit to return.

Batting

Main article: batting (cricket)

At any one time, there are two batsmen in the playing area. One takes station at the striker's end to defend the wicket as above and to score runs if possible. His partner, the non-striker, is at the end where the bowler is operating.

Batsmen come in to bat in a batting order, decided by the team captain. The first two batsmen – the "openers" – usually face the hostile bowling from fresh fast bowlers with a new ball. The top batting positions are usually given to the most competent batsmen in the team, and the team's bowlers – who are typically, but not always, less skilled as batsmen – typically bat last. The pre-announced batting order is not mandatory; when a wicket falls any player who has not yet batted may be sent in next.

If a batsman "retires" (usually due to injury) and cannot return, he is actually "not out" and his retirement does not count as a dismissal, though in effect he has been dismissed because his innings is over. Substitute batsmen are not allowed.

A skilled batsman can use a wide array of "shots" or "strokes" in both defensive and attacking mode. The idea is to hit the ball to best effect with the flat surface of the bat's blade. If the ball touches the side of the bat it is called an "edge". Batsmen do not always seek to hit the ball as hard as possible, and a good player can score runs just by making a deft stroke with a turn of the wrists or by simply "blocking" the ball but directing it away from fielders so that he has time to take a run.

There is a wide variety of shots played in cricket. The batsman's repertoire includes strokes named according to the style of swing and the direction aimed: e.g., "cut", "drive", "hook", "pull".

A batsman is not required to play a shot; in the event that he believes the ball will not hit his wicket and there is no opportunity to score runs, he can "leave" the ball to go through to the wicketkeeper. Equally, he does not have to attempt a run when he hits the ball with his bat. He can deliberately use his leg to block the ball and thereby "pad it away" but this is risky because of the leg before wicket rule.

In the event of an injured batsman being fit to bat but not to run, the umpires and the fielding captain were previously able to allow another member of the batting side to be a runner. The runner's only task was to run between the wickets instead of the incapacitated batsman, and he was required to wear and carry exactly the same equipment as the batsman. As of 2011 the ICC outlawed the use of runners as they felt this was being abused.[27]

Runs

Main article: Run (cricket)

The primary concern of the batsman on strike (i.e., the "striker") is to prevent the ball hitting the wicket and secondarily to score runs by hitting the ball with his bat so that he and his partner have time to run from one end of the pitch to the other before the fielding side can return the ball. To register a run, both runners must touch the ground behind the crease with either their bats or their bodies (the batsmen carry their bats as they run). Each completed run increments the score.

More than one run can be scored from a single hit; but, while hits worth one to three runs are common, the size of the field is such that it is usually difficult to run four or more. To compensate for this, hits that reach the boundary of the field are automatically awarded four runs if the ball touches the ground en route to the boundary or six runs if the ball clears the boundary without touching the ground within the boundary. The batsmen do not need to run if the ball reaches or crosses the boundary.

Hits for five are unusual and generally rely on the help of "overthrows" by a fielder returning the ball. If an odd number of runs is scored by the striker, the two batsmen have changed ends, and the one who was non-striker is now the striker. Only the striker can score individual runs, but all runs are added to the team's total.

The decision to attempt a run is ideally made by the batsman who has the better view of the ball's progress, and this is communicated by calling: "yes", "no" and "wait" are often heard.

Running is a calculated risk because if a fielder breaks the wicket with the ball while the nearest batsman is out of his ground (i.e., he does not have part of his body or bat in contact with the ground behind the popping crease), the batsman is run out.

A team's score is reported in terms of the number of runs scored and the number of batsmen that have been dismissed. For example, if five batsmen are out and the team has scored 224 runs, they are said to have scored 224 for the loss of 5 wickets (commonly shortened to "224 for five" and written 224/5 or, in Australia, "five for 224" and 5/224).

Extras

Main article: Extra (cricket)

Additional runs can be gained by the batting team as extras (called "sundries" in Australia) due to errors made by the fielding side. This is achieved in four ways:

- No ball: a penalty of one extra that is conceded by the bowler if he breaks the rules of bowling either by (a) using an inappropriate arm action; (b) overstepping the popping crease; (c) having a foot outside the return crease. In addition, the bowler has to re-bowl the ball. In limited overs matches, a no ball is called if the bowling team's field setting fails to comply with the restrictions. In shorter formats of the game (20–20, ODI) the free hit rule has been introduced. The ball following a front foot no-ball will be a free-hit for the batsman, whereby he is safe from losing his wicket except for being run-out.

- Wide: a penalty of one extra that is conceded by the bowler if he bowls so that the ball is out of the batsman's reach; as with a no ball, a wide must be re-bowled. If a wide ball crosses the boundary, five runs are awarded to the batting side (one run for the wide, and four for the boundary).

- Bye: extra(s) awarded if the batsman misses the ball and it goes past the wicketkeeper to give the batsmen time to run in the conventional way (note that one mark of a good wicketkeeper is one who restricts the tally of byes to a minimum).

- Leg bye: extra(s) awarded if the ball hits the batsman's body, but not his bat, while attempting a legitimate shot, and it goes away from the fielders to give the batsmen time to run in the conventional way.

When the bowler has bowled a no ball or a wide, his team incurs an additional penalty because that ball (i.e., delivery) has to be bowled again and hence the batting side has the opportunity to score more runs from this extra ball. The batsmen have to run (i.e., unless the ball goes to the boundary for four) to claim byes and leg byes but these only count towards the team total, not to the striker's individual total for which runs must be scored off the bat.

Dismissals

Main article: Dismissal (cricket)

There are eleven ways in which a batsman can be dismissed; five relatively common and six extremely rare. The common forms of dismissal are "bowled", "caught", "leg before wicket" (lbw), "run out", and "stumped". Less common methods are "hit wicket", "hit the ball twice", "obstructed the field", "handled the ball" and "timed out" – these are almost unknown in the professional game. The eleventh - retired out - is not treated as an on-field dismissal but rather a retrospective one for which no fielder is credited.

If the dismissal is obvious (for example when "bowled" and in most cases of "caught") the batsman will voluntarily leave the field without the umpire needing to dismiss them. Otherwise before the umpire will award a dismissal and declare the batsman to be out, a member of the fielding side (generally the bowler) must "appeal". This is invariably done by asking (or shouting) "how's that?" – normally reduced to howzat? If the umpire agrees with the appeal, he will raise a forefinger and say "Out!". Otherwise he will shake his head and say "Not out". Appeals are particularly loud when the circumstances of the claimed dismissal are unclear, as is always the case with lbw and often with run outs and stumpings.

- Bowled: the bowler has hit the wicket with the delivery and the wicket has "broken" with at least one bail being dislodged (note that if the ball hits the wicket without dislodging a bail it is not out).[28]

- Caught: the batsman has hit the ball with his bat, or with his hand which was holding the bat, and the ball has been caught before it has touched the ground by a member of the fielding side.[29]

- Leg before wicket (lbw): the ball has hit the batsman's body (including his clothing, pads etc. but not the bat, or a hand holding the bat) when it would have gone on to hit the stumps. This rule exists mainly to prevent the batsman from guarding his wicket with his legs instead of the bat. To be given out lbw, the ball must not bounce outside leg stump or strike the batsmen outside the line of leg-stump. It may bounce outside off-stump. The batsman may only be dismissed lbw by a ball striking him outside the line of off-stump if he has not made a genuine attempt to play the ball with his bat.[30]

- Run out: a member of the fielding side has broken or "put down" the wicket with the ball while the nearest batsman was out of his ground; this usually occurs by means of an accurate throw to the wicket while the batsmen are attempting a run, although a batsman can be given out Run out even when he is not attempting a run; he merely needs to be out of his ground.[31]

- Stumped is similar except that it is done by the wicketkeeper after the batsman has missed the bowled ball and has stepped out of his ground, and is not attempting a run.[32]

- Hit wicket: a batsman is out hit wicket if he dislodges one or both bails with his bat, person, clothing or equipment in the act of receiving a ball, or in setting off for a run having just received a ball.[33]

- Hit the ball twice is very unusual and was introduced as a safety measure to counter dangerous play and protect the fielders. The batsman may legally play the ball a second time only to stop the ball hitting the wicket after he has already played it. "Hit" does not necessarily refer to the batsman's bat.[34]

- Obstructing the field: another unusual dismissal which tends to involve a batsman deliberately getting in the way (physically and/or verbally) of a fielder.[35]

- Handled the ball: a batsman must not deliberately touch the ball with his hand, for example to protect his wicket. Note that the batsman's hand or glove counts as part of the bat while the hand is holding the bat, so batsmen are frequently caught off their gloves (i.e. the ball hits, and is deflected by, the glove and can then be caught).[36]

- Timed out usually means that the next batsman was not ready to receive a delivery within three minutes of the previous one being dismissed.[37]

In the vast majority of cases, it is the striker who is out when a dismissal occurs. If the non-striker is dismissed it is usually by being run out, but he could also be dismissed for obstructing the field, handling the ball or being timed out.

A batsman may leave the field without being dismissed. If injured or taken ill the batsman may temporarily retire, and be replaced by the next batsman. This is recorded as retired hurt or retired ill. The retiring batsman is not out, and may resume the innings later. An unimpaired batsman may retire, and this is treated as being dismissed retired out; no player is credited with the dismissal. Batsmen cannot be out bowled, caught, leg before wicket, stumped or hit wicket off a no ball. They cannot be out bowled, caught, leg before wicket, or hit the ball twice off a wide. Some of these modes of dismissal can occur without the bowler bowling a delivery. The batsman who is not on strike may be run out by the bowler if he leaves his crease before the bowler bowls, and a batsman can be out obstructing the field or retired out at any time. Timed out is, by its nature, a dismissal without a delivery. With all other modes of dismissal, only one batsman can be dismissed per ball bowled.

Innings closed

Main article: End of an innings (cricket)

An innings is closed when:

- Ten of the eleven batsmen are out (have been dismissed); in this case, the team is said to be "all out"

- The team has only one batsman left who can bat, one or more of the remaining players being unavailable owing to injury, illness or absence; again, the team is said to be "all out"

- The team batting last reaches the score required to win the match

- The predetermined number of overs has been bowled (in a one-day match only, commonly 50 overs; or 20 in Twenty20)

- A captain declares his team's innings closed while at least two of his batsmen are not out (this does not apply in one-day limited over matches)

Results

Main article: Result (cricket)

If the team that bats last is all out having scored fewer runs than their opponents, the team is said to have "lost by n runs" (where n is the difference between the number of runs scored by the teams). If the team that bats last scores enough runs to win, it is said to have "won by n wickets", where n is the number of wickets left to fall. For instance a team that passes its opponents' score having only lost six wickets would have won "by four wickets".

In a two-innings-a-side match, one team's combined first and second innings total may be less than the other side's first innings total. The team with the greater score is then said to have won by an innings and n runs, and does not need to bat again: n is the difference between the two teams' aggregate scores.

If the team batting last is all out, and both sides have scored the same number of runs, then the match is a tie; this result is quite rare in matches of two innings a side. In the traditional form of the game, if the time allotted for the match expires before either side can win, then the game is declared a draw.

If the match has only a single innings per side, then a maximum number of deliveries for each innings is often imposed. Such a match is called a "limited overs" or "one-day" match, and the side scoring more runs wins regardless of the number of wickets lost, so that a draw cannot occur. If this kind of match is temporarily interrupted by bad weather, then a complex mathematical formula, known as the Duckworth-Lewis method after its developers, is often used to recalculate a new target score. A one-day match can also be declared a "no-result" if fewer than a previously agreed number of overs have been bowled by either team, in circumstances that make normal resumption of play impossible; for example, wet weather.

No comments:

Post a Comment